I Still Believe in Love

Three kinds of Love the World Needs Now

Years ago, while complaining to a friend about someone, he responded, after listening to my tirade, “Well, you know Jim, most people are doing the best they can with what they have and who they are.”

That sentence froze me in my tracks, and it has stayed with me through the years.

Every time, ok, that's not true. Most of the time. When I encounter someone challenging, upsetting, and frustrating, I pause and attempt to recall that phrase. "Most people are doing the best they can…" It helps me remember something foundational to life as a human being. Namely, that we are all broken, flawed, and wounded people. It also helps me pause and remember that my frustration might have more to do with me than with others.

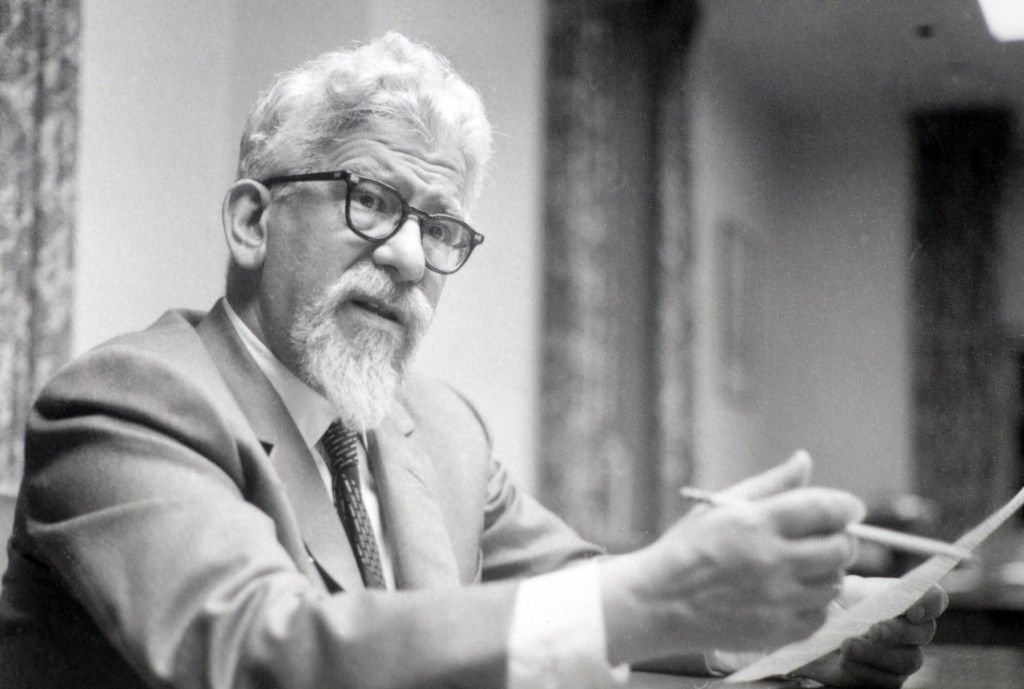

In psychological terms, this is called “projection.” The basic idea is that we project onto another person our shortcomings. But, of course, it's a bit more than that, and you can read a summary on Daryl Sharp’s Lexicon here. Just scroll down to Projection. But you get the idea, or maybe you don’t.

Jesus expressed it well in this parable.

He also told them a parable: “Can a blind person guide a blind person? Will not both fall into a pit? A disciple is not above the teacher, but every disciple who is fully qualified will be like the teacher. Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye but do not notice the log in your own eye? Or how can you say to your neighbor, ‘Friend, let me take out the speck in your eye,’ when you yourself do not see the log in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor’s eye. Luke 6:39-42

This is another way of getting at “most people are doing the best they can.”

In the last few weeks, I've been delivering sermons in various congregations on the subject of love. It seems that what the world needs now is love – more than ever. Shall I list all the reasons why I believe we need love? You know them. You see them everywhere, from your screens to newspapers, to personal encounters at work or in the grocery store. And the recent events in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, NY are two more examples. My Lord, how long, how long? For a sobering account of school shootings in America, read here.

But if the world needs love now more than ever, we in the English-speaking world have a love problem. Our vocabulary is limited, and one wonders if this limited vocabulary may be connected to our limited ability to exercise and practice love. Our limitations center around having only one word for love. Yet, we use that exact same word for various expressions of love. Consider the variety of meanings behind the word love in these sayings. I love my children. We love our house. I love my new car, oh I love this suit or this dress, don't you love that new song? I've been a Red Sox fan forever. I just love them. Hopefully, we don't view that love of a piece of clothing the same way we love our children.

In Sanskrit, there are 96 words for love. In ancient Persian, there were 80, and in Greek, there are three, but in English, we have only one. I recently learned that the Eskimo people have 30 different words for snow. They find such nuance in the varieties of snow they are compelled to have a vocabulary equal to their environment. Perhaps if we had more words for love, we would be better at its manifestation in our environment.

The Greek language might help us. This ancient language which helped shape western culture, philosophy, democracy, and religion, specifically Christianity, had three words for love.

1. Eros refers to passionate love.

While some have associated this word exclusively with eroticism and therefore given it a solely sexual meaning, that would be a mistake. Yes, there is erotic love that is sexual, but underneath eros is something more like passion. Eros is the driver, perhaps the instinctual mover in life. What gives you that energy to launch a new venture, whether to begin an artwork or fight for a social justice cause. That's eros at work in you. We need Eros love these days. It has a powerful feeling component. In one of her final lectures, Psychologist Marie Louise Von Franz lamented the loss of the feeling function in Western Society. She understood Eros has that energy that drives people into connection or relatedness. As an expression of love, the recovery of Eroscould help us mend our discordant dialogue, our failure to deeply grieve, and our chronic loneliness, which some have described as the root of many of our problems. We need Eros love now more than ever because it will give power to right wrongs, and energy to engage with one another.

2. Philos means warm affection or friendship.

Philos was commonly used concerning friendships or family relationships. When describing this type of love, I often ask people to think of English words that begin with Philo or Phila. Inevitably, someone says Philadelphia, formerly called the city of brotherly love. Today we might broaden that to make it less gender-specific. The idea of comradeship, friendship, and companions on life's pilgrim might be other ways of describing this Philos love. For example, Philos was the word used for Jesus' love for His friend Lazarus (John 11:3,36) and His love for His disciple (John 20:2).

Each year I spend a week with seven men. We have been friends for 40 years, since first meeting in the early 1980s while working as summer camp counselors and environmental educators at a Lutheran Camp in Southern California. The week together involves bicycling great distances, camping in tents, telling stories, and laughter. Amid all the fun and frivolity, we explore the wounds, disappointments, and sorrows of our lives. I described this once to a group of women, and they all said, “I wish my husband had something like that, he’s so isolated.” I thought to myself, “I know, it is such a rare gift for men in our competitive society. I’m grateful for it, and I too wish more men and women could experience a group of comrades who will walk through life with one another.” We need Philos love now more than ever.

3. Agapē is unconditional love.

This kind of love is challenging for human beings to express because we live in such a conditional and transactional society. Agapē is often used in the New Testament to describe an unconditional love between God and humanity. Agapē is the word for love used in 1 Corinthians 13. Often read at weddings, but it's even more potent at a funeral, as I previously described. If we are fortunate, we get a glimpse of unconditional love during our lifetime, perhaps from a friend, a parent, or a spouse. One person described her experience of unconditional love coming to her from her pet dog of 13 years. She felt completely accepted for who she was by this animal. Non-dog lovers might scratch their head at that one, but others with pets know the experience.

Agape love relates to the holy, the sacred, and the mystical. This is the kind of love St. Tereasa of Avilla describes, or Julian of Norwich when she prays that delightful prayer, “All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.” We need Agape love now more than ever.

Julian pictured with a Cat, since I gave a shout out to the Dog-Lovers, I thought it was only fair to offer equal time.

"Most people are doing the best they can with what they have and who they are." That's a mantra worth repeating for a world that needs love now more than ever.